01

Editor’s Note

Sohini Bhattacharya

Every year, when September 5 comes around, we see articles on Savitribai Phule in newspapers as the first woman teacher in India. Savitribai was also a feminist, a social reformer and activist, a voice against caste discrimination, a philanthropist and a poet-everything that a teacher could aspire to be and every role that a teacher can easily play within a school system. In our work within the government school system across six states in north India, we have seen teachers playing these roles time and again. Be it Hema* didi who stops the underage marriage of a girl in Uttar Pradesh, or Sanjay* bhaiya who spends his own money to send a poor girl in Jharkhand to a higher secondary school, or Jitender* sir who wrote a poem on girl power in Punjab, or the ASHA didi, Sarita*, who lashed out against gender-based sex selection in Haryana. The unsung teachers who not only teach but also build the infrastructure for holistic education in our country are often nameless and faceless.

In Breakthrough’s work, we have found teachers our biggest allies when talking about gender transformative schools. We have, so far, trained more than 1,500 master trainers in Punjab on how to deliver gender-infused curriculums in government middle schools, leading to 23,000 teachers being trained across the state initially. The stories that come out from those training sessions also reflect their life stories of being women in patriarchal setups.

*Names changed

THE LEDE

02

Teachers are the lever for ushering in gender transformative school systems anywhere in the world. They are central to the education system for the key roles they play in the transmission of values, knowledge, and the development of human potential and skills. Teachers are influential members of their communities due to their access to the government system and resources, their role in most last-mile initiatives (vaccination drives, voter ID registration, etc.), their strength in numbers and in their ability to influence the thinking and behaviour of adolescents.

lens. Teachers should be aware of gender roles and gender-based discrimination in classrooms; they need not differentiate between boys and girls in classroom settings; they continue to have increased conversations with girl students to support/encourage them to continue their education; they abstain from using gender and/or casteist slurs in addressing students; they should continue asking girls more questions and push them towards STEM education; they should encourage girls to play sports and have a career.

The teachers’ own attitudes towards gender norms and their inability to engage in critical dialogue about gender inequality within classrooms or when approached by students with curious questions around existing gender norms is one of the key challenges in their demonstration of gender positive approaches in their interaction with students. Traditional meanings regarding masculine and the feminine persist and continue to be reaffirmed by the teachers’ behaviours and attitudes. There is a need to nudge teachers towards more gender-equitable behaviour in the classroom, make sure that such behaviours are incentivised and recognised, and that there is complete buy-in from the authorities.

While concepts and theories on gender might be included in the teacher training curriculum, teachers need to learn to examine and understand how gender is constructed and how it affects the lives of women and girls by drawing upon their own life experiences and by building their capacities on examining these experiences critically through a gender

THE LEDE

03

Teachers are the lever for ushering in gender transformative school systems anywhere in the world. They are central to the education system for the key roles they play in the transmission of values, knowledge, and the development of human potential and skills. Teachers are influential members of their communities due to their access to the government system and resources, their role in most last-mile initiatives (vaccination drives, voter ID registration, etc.), their strength in numbers and in their ability to influence the thinking and behaviour of adolescents.

The teachers’ own attitudes towards gender norms and their inability to engage in critical dialogue about gender inequality within classrooms or when approached by students with curious questions around existing gender norms is one of the key challenges in their demonstration of gender positive approaches in their interaction with students. Traditional meanings regarding masculine and the feminine persist and continue to be reaffirmed by the teachers’ behaviours and attitudes. There is a need to nudge teachers towards more gender-equitable behaviour in the classroom, make sure that such behaviours are incentivised and recognised, and that there is complete buy-in from the authorities.

While concepts and theories on gender might be included in the teacher training curriculum, teachers need to learn to examine and understand how gender is constructed and how it affects the lives of women and girls by drawing upon their own life experiences and by building their capacities on examining these experiences critically through a gender lens. Teachers should be aware of gender roles and gender-based discrimination in classrooms; they need not differentiate between boys and girls in classroom settings; they continue to have increased conversations with girl students to support/encourage them to continue their education; they abstain from using gender and/or casteist slurs in addressing students; they should continue asking girls more questions and push them towards STEM education; they should encourage girls to play sports and have a career.

THE LEDE

03

The block and district level education departments and Cluster Resource Centres (CRC) are the most important spaces for teachers’ empowerment. This is where teachers share notes on innovative learning tools and practices. There are assigned human resources within these structures like DEOs and BEOS, Cluster Coordinators and Master Trainers who are tasked with training and monitoring the activities of the teachers also. This is where the school system needs to become a gender transformative system – gendered barriers are considered as root causes when administrators design their interactions with teachers; spaces are created for individuals to actively challenge gender norms; power inequities between persons of different genders within the system become points of consideration and gender related outcomes and impacts are monitored regularly.

The other problem in this whole system is the roles of the women teachers within the system. When it comes to school leadership, a 2018 National Institute of Educational Planning and Administration (NIEΡΑ) report shows that 13 states and Union Territories have a higher or equal representation of women as acting heads, vice-principals, and principals and are under-represented in 19 states. Interestingly, 20 states see more women as vice-principals than principals. The factors coming in the way for women range from school managements refusing to have a woman lead it to a perceived higher degree of family commitments of women, to the downright refusal of some women to take leadership roles, For progressive gendered policy to be implemented successfully, a dynamic shift in approach within such a system is required. From that of the school administrator to the teacher, to the adolescent in the classroom, the learner must develop an ability to question relations of power in society, as

well as an ability to overcome the disadvantages of discrimination and unequal socialisation. This edition of Engendered Education focuses on teachers-those Savitribais who have the power to change the world. The ‘cover story’ is authored by Adhishree Parasnis, the director of communications at Global School Leaders, and her team who have extensively worked towards providing quality training to school leaders in underserved communities across the world. Adhishree highlights key examples of gender transformative leadership across the world, especially one that intersects with caste as well. There is a Q&A with Anita Bharti, an educator from the northern Indian Hindi belt who talks to us about approaching education as a Dalit and challenging hegemony in educational material in Indian schools. Ritwik Chakravarty, a young queer educator and trainer who works with Humsafar Support Centre for Women, Youth, and Queer in Lucknow has also contributed to this issue. For the last four years, Ritu has been designing educational material for children from underserved communities, especially in Hindi, that expands Indian regional languages and brings inclusivity in terms of queer identities and expression. Their work also challenges gender binaries in the school education curriculum.

Enjoy reading the perspectives of these diverse educators!

Sohini Bhattacharya

Editor-in-Chief, Engendering Education

THE LEDE

04

The

Elephant in

the Room

Ritwik Chakravarty

Indian school textbooks have long suffered an unsettling truth: That they’re deeply gendered and sexist. A survey in the 1970s, which assessed nearly 200 Indian school lessons, found not just lack of gender representation but also one that fuels gender bias in societies. Ritwik Chakravarty grew up reading some of those stories but they refused to accept them. Today, the 26-year-old is part of a grassroots movement that not only challenges everyday gender bias in classrooms but also does so with intersectionality. Chakravarty joins the second edition of Engendering Education to talk about how small radical acts of transformative education can create a healthy society.

CLOSE UP

05

It was Chandni, the goat, that first caught Ritwik Chakravarty’s fascination – and despair.

“Chandni”, a story in India’s Central Board of Secondary Education syllabus, is about a goat called Chandni who longs to break free from her master, a man called Abbu Khan. After several attempts to restrain her, Khan releases Chandni into the wild. For a few sunny hours, Chandni embraces freedom. But then the night falls and she is attacked by a wolf. After a fierce battle, Chandni is killed but the birds in the vicinity who witness the fight say the wolf may have won the fight, but Chandni was the real winner.

As a teen, Chakravarty was enamoured by Chandni’s passion for freedom. But the teacher who taught this class had a different conclusion.

“Our teacher turned to us and said we should always listen to our elders, and that this is what happens to those who ask for freedom,” they told Engendering Education in an interview. “This story that celebrated a virtue like freedom was distorted into a cautionary tale. I was just about 13. Even by then, I had a strong sense that there was something wrong with that kind of teaching. In fact, I stood up and said that if all other goats had run away like Chandni in that story, no wolf would be able to take them down.”

“I look at education just like that: A collective effort that can bring us freedom,” they added.

Chakravarty is an educator, trainer and the senior program officer at Humsafar Support Centre for Women, Youth and Queer Persons in Crisis. The organisation was set up in 2003 in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh as a response against

discrimination and violence across the sexual spectrum on the basis of gender, religion, caste and class. Since 2003, the organisation has provided support to over 9,000 survivors. They have also, at the same time, been working towards gender equality and equity across several underserved communities and schools of the capital city of Lucknow.

26-year-old Chakravarty has been in the education sector for the last four years, but their work is vastly informed by their misadventures in classrooms, prompting them to work towards reversing patriarchal tropes and gender binaries in existing curriculums. In Lucknow, Chakravarty spends a large part of their time engaging with underserved communities and designing classroom activities that challenge stereotypes and biases firmly set in the school books.

“Our education system tends to re-confirm gender biases and binaries in a very visible way,” they said. “Gender binaries are steeped in education material for kids as young as in nursery. They’re learning stuff like ‘Papa ka hain paisa gol, mummy ki hain roti gol [Round is the shape of father’s money, just like the shape of mother’s rotis]. It’s been enshrined in that young child that the father is the financial source and the mother is restricted to the kitchen. This directly translates to the respect we give to both of them.”

Gender stereotypes in education material have been a problem for ages. A 2021 study by Carnegie Mellon University and the University of Wisconsin-Madison, which analysed 247 children’s books, reiterated that early education books, which play an integral role in solidifying gendered perceptions in young children, have been deepening those perceptions even further.1

Women and girls are

massively underrepresented

in school textbooks, or when

included, are depicted in

traditional roles.

A 2020 Global Education Monitoring Report by UNESCO.2

CLOSE UP

06

In fact, children’s books, the research found, have more gendered stereotypes than fictional books read by adults.

In India, a definitive – albeit controversial – study was done by professor Narendra Nath Kalia way back in the 1970s that showed that Indian school textbooks aren’t just sexist but also riddled with “obscurantist tendencies”.3 Kalia, who taught Sociology at the State University College in Buffalo, New York, had screened 20 Hindi and 21 English language textbooks for classes 9th to 11th in Delhi, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Punjab and Haryana. At least 13 lakh students were, annually, using the 188 lessons that were sampled in the study, which showed that 60 percent of the 114 lessons had males as the lead characters, while only 6.9 percent of them had women as central characters, Another example of gendered language is a textbook story called “Resignation”, which had this line: “There was a disappointment and defeat all around him. He had no son, but three daughters; no brother but two sisters-in-law.”

This study came on the heels of India’s pivotal educational policy revamp in 1965 that promised to discard gender biases in school textbooks. But the work of Kalia, who also authored Lies We Tell Our Children: Sexism in Indian Education (1982), not only exposed the gaps in these promises, but also led to the National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT) making revisions in those textbooks.

Over the years, there have been tremendous efforts to right the wrongs. In 2021, NCERT released a teachers’ training manual to address gender disparity in education, although the move quickly received backlash, saying such gender sensitisation content might be a “conspiracy” to traumatise students.4 Another effort to introduce gender neutral reforms such as common uniforms for all genders and mixed seatings in classrooms in Kerala, in 2022, was cancelled due to protests by conservative organisations, In 2022, Breakthrough introduced gender equity curriculum in social studies books from classes 6th to 8th, while also training 250 master trainers.5

Chakravarty is part of the grassroots mavement in India that is working on alternative methods to shape the act of learning. Armed with a Masters in Social Work, Gender and Sexuality from Dr Shakuntala Misra

National Rehabilitation University in Uttar Pradesh, Chakravarty has been working closely with hundreds of children, mostly teenagers, to not just go through school textbooks, but also play around with them.

“The fundamentals of most of our educational material are structurally wrong but educators have the power to subvert even the most deep-seated biases,” they said. “For instance, I took the nursery rhyme I mentioned before and, for my lessons with the students I engage with, I turned it to: ‘Dekho apni duniya hain gol, matar ki kachori papa ne bele hain gol, mummy daftar jab jaati hai pehne woh chashma gol, Asif ke kaano main dekho jhumke hain gol, Riya ke shirt ke button hain gol… [Look, our world is round, just like the round kachoris father makes, just like the spectacles mother wears at work, just like Asif’s earrings, and the buttons on Riya’s shirt] and so on.”

“These methods are created to show that such diverse identities and expressions exist,” they said, adding that their main work is largely in Hindi, which is the language of the masses in the country’s most populous state. For this, they invoke the works of pioneering educator Savita bai Phule, who, in one of her poems, urged people learn English to escape the caste discrimination that’s deeply entrenched in Indian languages.6

CLOSE UP

07

Another inspiration is the late award-winning feminist scholar Sharmila Rege, who developed the Dalit standpoint perspective in feminist debates, and also fought for the right to education of Dalit students. Chakravarty highlights the role of her essay called ‘Dalit Women Talk Differently’ 6 in informing their own curriculum design and workshops, in the way they assert the need to create another language to make the existing discourse on education intersectional.

“I agree with this but I also believe that the privilege hasn’t arrived here yet. But that doesn’t mean we stop working. If there’s no option, then we create pathways to expand our language. If the expression of my caste doesn’t exist in your language and all the

words are slurs, then we will change that language and make space for myself.”

India banned caste-based hate crimes of untouchability, discrimination, slurs and violence in 1950, but one of the many spaces this violence has persisted is the classrooms. Across India, there has been a rise in reported cases of dominant caste teachers being arrested for killing Dalit students, or beating them, or using caste-based slurs against them. There’s no data for primary schools but an official survey shows that Dalit and indigenous people account for less than 5 percent of teaching roles in higher Indian education.7

The two key themes that Chakravarty works on are gender and constitutional values. The Indian Constitution, they say, is important because it opens conversations up to caste and class.

But Chakravarty’s introduction to gender starts with themself. They are a non-binary trans feminine educator, and most often, their appearance leaves a lot of room for curiosity. In their classrooms, in fact, Chakravarty identifies as Ritu. “It’s the first thing that people ask me when I go to the communities for gender training, you know,” they said. “”Aap kya hain [What are you]? You’re not fully male or fully woman.” Ritu is the name closest to their birth name. But there’s more to it: “Ritu means weather,” they added. “And I’m like the weather. It’s not constant, it’s fluid and it’s unpredictable. I use my name as a tool to sensitise the communities.”

There’s a big misconception that underserved communities don’t understand intersectional language, they added, and that it’s up to the privileged castes and class to “educate” them. “That’s simply not true,” they said. “They speak a simpler language that is often lost in complex NGO jargon. The women from these communities speak a language of intersectional solidarity and sisterhood that you will not find anywhere. They challenge patriarchy every day.” Teachers, they added, need to unlearn the violence and patriarchy in their own language. “Otherwise, no matter how much of a feminist you are, you can’t communicate effectively,” they said.

CLOSE UP

08

The politics of talking about caste and gender can be a touchy subject in India. Chakravarty said they are often told to “not be too political” in their engagements in schools in Lucknow. But it’s the larger system they want to fight through their work, and not just one-off schools. They are advocating for intersectional and diverse hiring, along with monitoring, auditing, and re-evaluations of curriculum, especially through the engagement of autonomous groups and organisations.

Most often, changes are introduced in reactionary ways, they said. “These are not structural. But education needs more structure building, and that can only happen if our society and norms are scrutinised,” they said.

Chakravarty says that teachers have a role bigger than just education. “When I assume the role of an educator, I’m not only responsible for my subject matter expertise, but also the language with which I’m conveying. Language is a powerful tool and I make sure that it’s accessible and I’m accountable for it.”

- Children’s Books Solidify Gender Stereotypes in Young Minds, Carnegie Mellon University (2021)

- Women under represented in school textbooks, shown mostly in traditional roles, Times of India (2020)

- Exposing the sharp bias against women in school textbooks in India, India Today (1980)

- Gender-Sensitive Training Manual May “Traumatize Students, Says a Complaint to Child Rights Body, The Swaddle, 2021

- When Savitribai urged women to learn English, Mid-day

- Dalit Women Talk Differently, Sharmila Rege, Economic and Political Weekly (1998)

- SCs and STs account for less than 5% of professors, Times of India (2019)

CLOSE UP

09

Beyond

the Glass

Ceiling

Adhishree Parasnis

Sanya Sagar

Tejas Airodi

Nearly two-thirds of the world’s teaching workforce is female. And yet, very few make it to the top. Research by Global School Leaders (GSL) – an international non-profit that aims to revolutionise learner and leadership mindsets – found that women school leaders have transformative impact in not just learning but also within teaching itself. For the second issue of Engendering Education, in which we celebrate the transformative legacy of Savitribai Phule, GSL’s Adhishree Parasnis, Sanya Sagar and Tejas Airodi pen down the exhaustive work that’s being done to create a gender-diverse school leadership that can transform not just teaching but societal norms as well.

COVER STORY

11

Emilly Otieno from Kenya once recounted to our team at Global School Leaders an incident in which a parent refused to speak to her because he said he does not “believe in women” in leadership positions. Otieno heads her school and while it was jarring for her to hear this negation of her seniority and experience, these beliefs are common in many of the contexts we work in.

Over the past seven years, we’ve worked with over 13,000 school leaders across nine countries including India, and we believe that school leadership lies at the heart of gender transformative education. Yet, time and again, we’ve seen how systems and societal norms thwart this potential of school leaders.

There’s a growing body of evidence that good school leadership can transform and disrupt inequitable patterns of learning. How can they do this? By actively monitoring and supporting instructional practices that cater to diverse learning needs, thus narrowing achievement gaps and creating an inclusive learning environment. They can also facilitate open lines of communication by encouraging parents or guardians to actively participate in their child’s education. By creating welcoming and inclusive spaces, they can ensure that all voices are heard, fostering a sense of belonging within the school community.

At the same time, there is ample global research illustrating how women school leaders are already doing this, and more.1 The 2018 ‘Teachers and School Leaders as Valued Professionals’ report found that women school leaders provide teachers with more instructional support (such as feedback) than male school leaders.2 They are also found to be more democratic in their approach by involving the voices of key stakeholders (teachers, families, and students) while making critical decisions that have a bearing on student experiences.3 Unsurprisingly, teachers under women leadership show better teacher attendance as well as higher engagement with students’ parents.4 Parents also tend to discuss their children’s behaviour and academic success more with female leaders.

GSL’s research confirms these global trends. In our recent 2023 ‘Promoting Understanding of Leadership in Schools’ (PULS) survey, female school leaders reported more effective communication with parents

and students, leading to lower dropout rates during the COVID-19 pandemic. A 2022 PULS survey found that female leaders placed a greater emphasis addressing the leaming loss caused by COVID-19 than their male counterparts. They were also more inclined to provide remedial classes for students who needed additional support.

What makes this promising data especially unfortunate is that even though teaching across the world is a feminised profession, particularly in the Global South, women’s representation in school leadership is disproportionately low.

In the African region (countries including Togo, Mali, Cote D’Ivoire, Burkina Faso, Niger, and Zambia), for instance, female teachers account for anywhere between 47-59 percent of the teaching population. But female school leaders make up 9 to 21 percent of the total.5 In India, while 48 to 52 percent of teachers in the schools with primary to secondary (1st to 10th standards) classes and schools with elementary classes (1st to 8th standards) were women, only 31 percent of them were designated headmistresses.6 Broadly, women school leaders only account for 26 percent of the total school leaders in low-income countries.7

99%

of Indian states

3 have unequal

representation

of women

designated as

headmistresses.8

COVER STORY

12

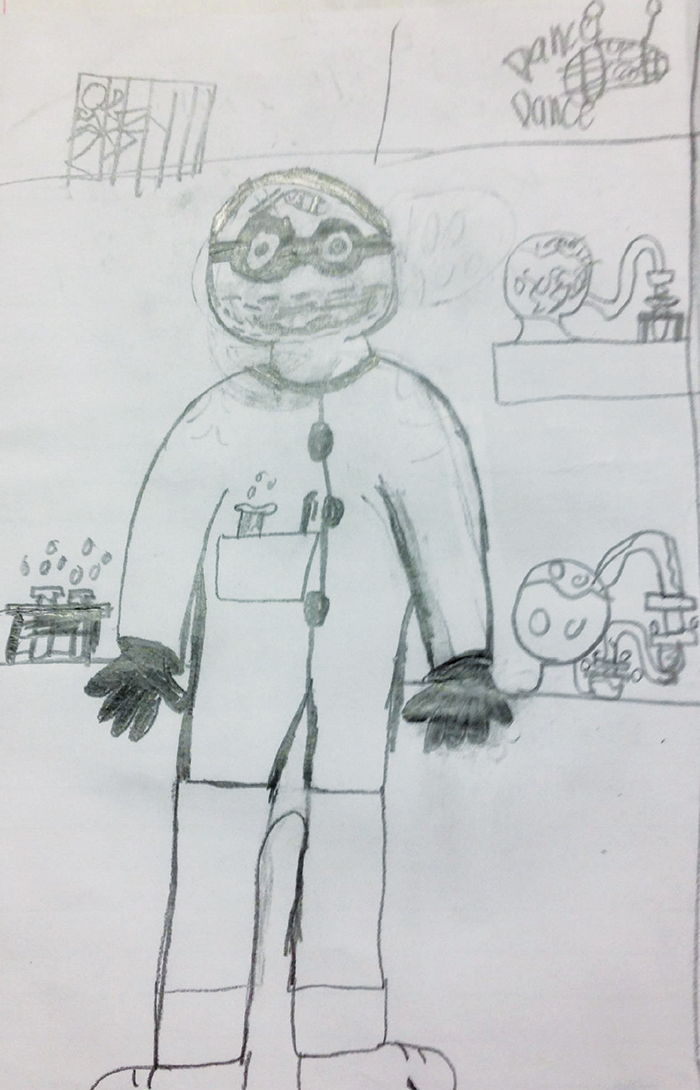

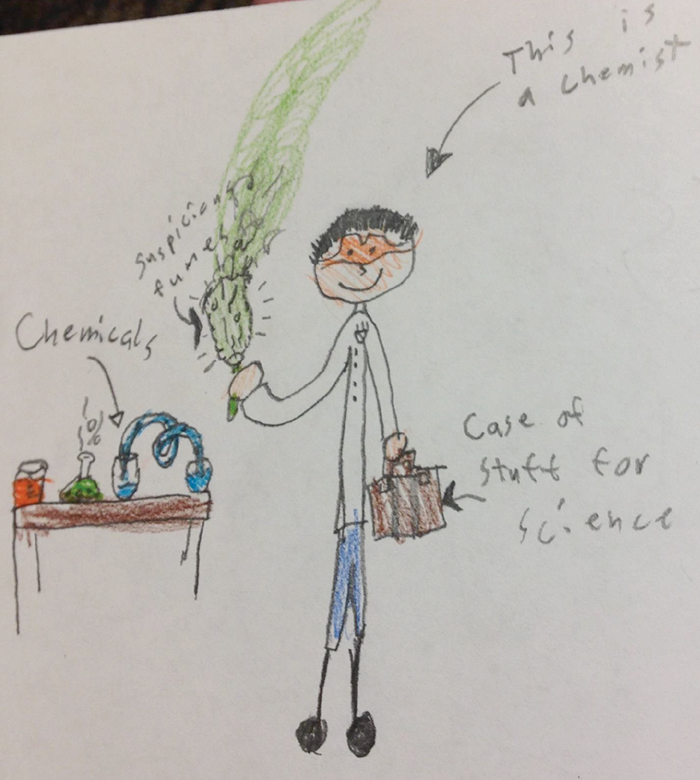

Image Courtesy: National Science Teaching Association

For 50 years, children took the ‘Draw a Scientist’ test, and overwhelmingly drew men as scientists over women.

This is significantly lower compared to representation in higher-income countries, where 56 percent of school leaders are women.9

This underrepresentation is symptomatic of the gender inequity perpetuated by our education systems School textbooks worldwide have commonly depicted women as caregivers and men as professionals. They associate certain traits, such as beauty, with girls and others, such as strength, with boys. Boys are told they must learn to make their voices heard, while girls are told they must leam to compromise for the sake of peace. Schools mirror societies,

The Draw-a-Scientist Test10 is a well-known study that has been conducted for the past 50 years in many countries including India, in which students are given prompts such as ‘Scientist’ and asked to draw. For 50 years, children have overwhelmingly drawn men as scientists rather than women.

Role models and subconscious messaging significantly impact shaping individuals’ beliefs and attitudes. Consequently, several countries have taken initiatives to develop more gender-equal textbooks. However, what is often overlooked is the need to examine and challenge the gender imbalance in the composition of a school’s staff and the gendered expectations imposed on the students. Who do students see in positions of leadership? What kind of values and traits do they see as important to being a leader? What does it tell them about who they can be? The disproportionately low representation of women in school leadership denies girls crucial role models.

In order to begin addressing gender inequity in education systems, we need leaders who collaborate, listen to all voices, prioritise communities, and support professional development. Excluding women from leadership limits the effectiveness of education systems by robbing them of diverse perspectives and equitable leadership.

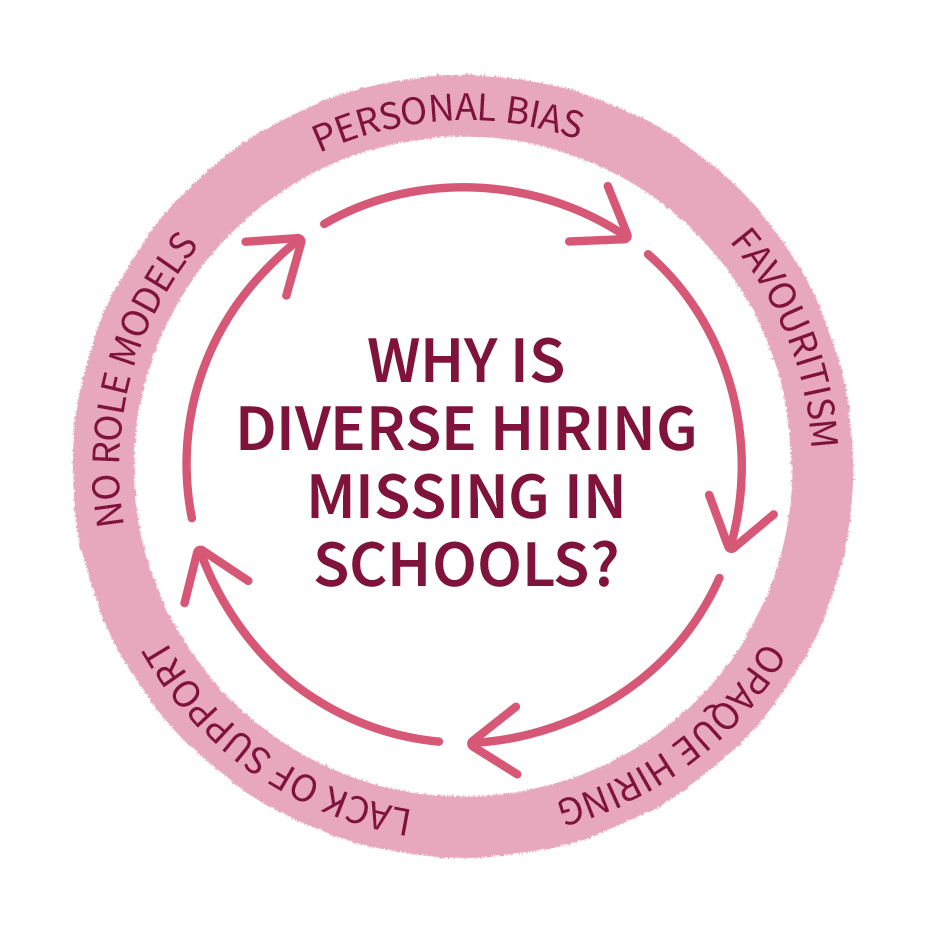

Before we can address this underrepresentation of women leaders, we need to deeply understand it.

To begin with, recruitment processes for school leadership positions are not always transparent in low-income countries.11 Personal biases, favouritism, dearth of objective selection criteria for appointments, and lack of support from other stakeholders towards promoting women make the processes out of reach for women.12 This, coupled with a lack of role models in the system, adds to the

COVER STORY

13

vicious cycle in which men continue to dominate leadership positions.

Much of society also sees leadership as the domain of men, as seen with the experiences of Emilly Otieno from Kenya. Other school leaders share that male staff often hesitate to take orders from a woman and that women have to fight negative stereotypes to be taken seriously. They must also fight internalised gender norms to see themselves capable of commanding authority. Add to that a lack of support from families and colleagues and unequal division of labour, and you have an environment where women are systematically kept away from leadership positions.

Another significant challenge is the scarcity of appropriate professional development opportunities, including training, networking, and mentorship designed to help women overcome barriers specific to their gender.13 The problem is compounded due to the lack of spaces where women can share their experiences, learn from each other and provide encouragement. Such gatherings would also allow women a safe space to reflect on their own beliefs and biases about themselves and other women. In many countries, absence of such spaces force women to rely on informal networks dominated by men.

What might be the way forward?

To increase women leadership representation, it’s imperative to enhance the transparency of appointment processes, which will demystify the selection criteria and promote inclusivity. Moreover, it’s crucial to implement diverse schemes and policies that go beyond mere encouragement, addressing potential barriers, and creating a supportive

framework that empowers women to confidently apply for and excel in leadership roles.

Secondly, it is also imperative to address negative and faulty beliefs about women leadership by providing school principals with opportunities to challenge school leaders’ own beliefs and mindsets in safe and supportive environments. This transformation can occur through various means such as training, mentorship, coaching, networking, and engagement within their peer communities. As GSL’s 2023 PULS survey found, merely having access to gender-responsive training does not necessarily correlate with a reduction in gender biases. Biases regarding student capabilities based on gender are still prevalent.

Training content should be deliberately designed to challenge existing beliefs and instill the idea that all students are equally capable of learning regardless of their gender. Moreover, the training or curriculum should empower school leaders to recognise the intricate factors contributing to gender inequity within their unique contexts, During the COVID-19 pandemic, we created Project Shakti (now known as Gender Equity Schools Project in partnership with Alokit), a program that prepares school leaders on gender-inclusive approaches to school re-enrollment of female students. This program tests two approaches to addressing learning inequity: One that encourages leaders to reflect on how gender influenced their own lives, decisions and beliefs, and the second on how this may impact their students.

Mentorship or coaching support, which involves consistent accountability, helps school leaders align

COVER STORY

14

about the gender disparities and barriers in school leadership roles across different contexts. Additionally, we’re trying to identify different enabling factors like access to coaching and training support and peer-to-peer networking opportunities for school leaders, and create policy action for implementation.

There’s a lot of work to do in the Global South in terms of building strong evidence of the barriers that impede progress toward gender equity in school leadership. It’s even more imperative now to document the role of gender-diverse school leaders in promoting gender-equitable outcomes, and for that, we need to understand the actions and strategies that are the most effective in creating equitable learning environments. This is work in progress, but one that will give answers to problems that persist beyond just classrooms.

- Increasing Women’s Representation in School Leadership: A promising path towards improving learning, UNICEF Office of Research (2022)

- Teachers and school leaders as valued professionals, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2020)

- Motivating the Nigerian academic and non-academic staff for sustainable higher education: Insights for policy options, Perspectives of Innovations, Economics and Business (2011)

- Time to Teach: Teacher attendance and time on task in West and Central Africa, UNICEF Office of Research (2020)

- Increasing Women’s Representation in School Leadership: A promising path towards improving learning, UNICEF Office of Research (2022)

- Representation of Women in School Leadership Positions in India, N Mythili (2017)

- Improving School Management in Low and Middle Income Countries: A Systematic Review (2023)

- *Representation of Women in School Leadership Positions in India, N Mythili (2017)

- Improving School Management in Low and Middle Income Countries: A Systematic Review (2023)

- What We Learn From 50 Years of Kids Drawing Scientists, The Atlantic (2018)

- “An Exploration of the influences of Female Under-representation in Senior Leadership Positions in Community Secondary Schools in Rural Tanzania (Unpublished doctoral dissertation] University College London (2015)

- Women and School Leaderships: Factors Deterring Female Teachers from Holding Principal Positions at Elementary Schools in Makassar (2011); Advancing Women in Leadership (2009); Ugandan Women: Moving Beyond Historical and Cultural Understanding of Educational Leadership; Women Leading Education Across the Continent, Sharing the Spinit, Fanning the Flame

- School leadership and gender in Africa: A systematic overview (2022); Voices of resilience: Female school principals, leadership skills, and decision-making techniques, South African Journal of Education (2020

COVER STORY

15

Image Courtesy: Mumbai Mirror

Remembering India's First Female Muslim Educator

This month marks the 193rd birthday of another pioneer of women’s education who worked closely with Savitribai Phule but about whom very little is known: Fatima Sheikh. Widely considered to be India’s first Muslim woman teacher and a social reformer, Sheikh is the co-founder – along with Phule – of the Indigenous Library, one of India’s first schools for girls that was built in 1848.

Born on January 9, 1831, in Pune, Sheikh shared an intimate camaraderie with Phule. Together, the two pioneers taught marginalised Dalit and Muslim women and children at a time when education was reserved mostly for upper-caste men, and women educators were unheard of. Sheikh was with Phule when upper-caste men pelted stones and cow dung while they were on their way to teach. A popular story goes that Sheikh and her brother Usman offered refuge to Savitribai and Jyotirao Phule when they were forced to leave their home in Pune because of the opposition they faced for educating Dalits and women. In fact, the Indigenous Library was opened in Sheikh’s house. Sheikh taught all the five schools that the Phules opened and worked there until 1856 when Phule fell sick and moved out to her mother’s home.

Sheikh’s story has long been overlooked but in 2014, the Indian government included her profile in Urdu textbooks of Bal Bharati Maharashtra State Bureau alongside other trailblazer peers such as Sir Syed Ahmad Khan and Abul Kalam Azad. Despite limited resources or information on her, modern-day educators give credit to Sheikh for a contribution that was truly intersectional, for which she is said to have faced double resistance and stigma as a woman and a Muslim. Two centuries later, her work continues to inform and inspire educators across India.

‘A Good Teacher Can Change Your Life’

Anita Bharti

When she was in secondary school, Anita Bharti experienced a personal setback. At one of Delhi’s public schools she was studying at, she saw her teachers routinely fling casteist slurs at students of oppressed castes, telling them they had no future. She then decided that no child will ever feel small under her care. Today, Bharti is one of the most revered educators in India’s capital city known for bringing her intersectional lens and empathy to classrooms. The 58-year-old has a rich legacy of achievements in her bag: Radhakrishnan Teacher Award (1994), Indira Gandhi teacher award (2007), the Delhi State Teacher’s Honor (2008) and three Savitribai Phule Awards. She opens up to Engendering Education on the critical need for caste and gender representation in Indian education.

CHANGE MAKER

17

Could you share your own journey of becoming an educator? What drew you to this field?

My journey officially started in 1992 when I got my first job as a Hindi lecturer. My work is very much informed by my own journey of learning, which started at one of the Municipal Corporation of Delhi schools for primary education in the capital city. This is at a time when these were the only schools in the city, especially for kids from the lower economic and caste communities. I remember that I was really good at studies, especially Hindi. Back then, teachers had this special commitment to teach and bond with children. I particularly remember one Lalita ma’am who would often make me sit on her lap because I was very short. I always looked forward to attending my school!

But when I started secondary school, the environment changed. I couldn’t do well in English and Math. I was a first-generation learner and students like me need a lot of care and attention, and more than anything, an expertise in child psychology. My English teacher was biased against non-English speaking kids. You see, even back then, you could see two types of students in government schools: Those whose families had been educated, and those who were first learners. This is where I saw a strange disgust in teachers towards the kids from oppressed communities. I came from the same community and that’s why I could never learn English because our teacher used to use casteist slurs and tell us, ‘What will you do with studying anyway?’ But later in 11th and 12th, I got a great Hindi teacher and kids used to respond to her very positively. This is how I got interested in teaching. Education sets the first foundation for anyone’s personality, and the one who sets that foundation is a teacher. A good teacher can change your life for good. Once I became a teacher, I knew that I’d never be like the teachers I got, and I would treat all kids equally.

Was teaching the only path you ever considered?

I originally wanted to be a social worker. When I was in college, I even ran my own school in a small way in my neighbourhood, where I gathered kids around me and taught them. My main passion has always been kids. I got admitted to the Delhi School of Social Work too but there were pressures at home that one has to earn a

degree that leads to a concrete job. And so I joined the education sector.

I feel I grew with the kids I was surrounded by, by just listening to them, honing their creativity. They truly energise me. There have been days when I’m feeling off and I just go to the primary section. Listening to them talk rejuvenates me!

I have, in my lifetime, seen many terrifying teachers because of whom I’ve lost interest in subjects. I’ve been rejected in classrooms due to teacher bias and lack of encouragement. This takes away the kids’ individuality and voices.

Who or what inspires you to be so committed to teaching?

CHANGE MAKER

18

and written about and translated her work. I feel that only those who have been held back from school or kept away from classrooms truly understand the real importance of education. It’s only through education that we’ve seen immense changes among the downtrodden communities in the last 50 years.

Could you share your thoughts on the kind of school books that are a part of the national curriculum? As a child, did you feel under or misrepresented in those textbooks?

How do you instil the lessons of equality in your classrooms despite such gaps in our textbooks?

I give some credit to slogans like “Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao”, which may have been politicised over the years but we still use it for gender training in classrooms. This slogan is rooted in reality, girls have been kept out of classrooms and even their ‘education’ wasn’t just about sending them to schools. Earlier, education for girls meant doing domestic work, reading religious scriptures and taking care of their husbands. Now, that meaning has changed – it means making girls self-sufficient and help them find a path for themselves. We’ve seen this in women who now have important posts in the country and are leading important conversations.

We also take current conversations to classrooms like

the debate between ‘Bharat’ and ‘India’ and we tell them that it’s two different words with one meaning. As teachers, it’s critical for us to impart secularist, anti-caste and anti-discriminatory principles.

But hasn’t talking about issues such as caste and the principles of secularism become sensitive these days?

Such topics aren’t a part of our syllabus. There’s a story called ‘Khanabadosh’ by Omprakash Valmiki in class 11th but it’s never taught from the lens of caste. And since this lens is not there, teachers often don’t know how to fight this kind of caste erasure. It’s like fighting a disease without knowing the symptoms. This erasure creates a perception that there’s no caste in India. But the bitter truth is that it’s there in abundance. If this caste system is done with, imagine where our country would be.

Right now, there’s a program called ‘Dignity of Labour’ in Delhi’s public schools where kids are encouraged to clean up after themselves and feel pride in that. However, in recent times, we’ve seen that the system of cleaning has been left on children entirely, which is the opposite of dignity of labour-us teachers have to clean with them. This program can easily turn caste-based too, where kids of certain communities are made to clean toilets. We need to look at the act of cleaning through the lens of dignity of labour. We also see instances of children refusing mid-day meals cooked by Dalit women in several states. So we need to instil this kind of sensitivity among children because they’re the ones who grow up to be the future citizens of our country.

CHANGE MAKER

19

Official data shows that Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe communities have less than 5 percent representation when it comes to teaching jobs in higher education. As someone who broke through this glass ceiling, could you talk about the importance of caste representation among educators?

I feel like there’s very little representation of first learners in education leadership. The reservation granted by our Constitution has played a big role in representation in schools but I still don’t feel this is enough. Fifty years of reservation is nothing in the face of around 250 years of discrimination our communities have faced. Despite this, our scarce visibility is resented by dominant caste communities. There’s a sense of entitlement among them that they deserve this job, or that there are too many of us in the system now. You only need to see the data published in the press, from journalism to judiciary and universities, to know we’re barely around in different sectors.

The reason why representation is important is because once we rise up in our fields, we can raise our voices for our communities. Over the centuries, the oppressed caste have been deprived of their resources, and generations have been going through trauma and torture. If you read the works of Omprakash Valmiki, Urmila Pawar, or Babytai Kamble, you’ll find details of this abuse and struggle. This is where the question of representation comes from.

Could you talk about whether or how educators are being trained to tackle the many problems in the system, and how much work is left to be done in this space?

Right now, we have teacher training on two levels, one on how to teach subjects and another on how to keep them engaged. Then there’s been a lot of leadership trainings that gives principals freedom on how to run

schools. This is important because in 2012, I had a bitter experience when I showed a film to my students and I was pulled up for that. A certain kind of freedom is necessary to hone decision-making by educators and give priority to what kids need. Gender sensitisation is also a big part of trainings now because there are so many questions around it. There are POCSO Act trainings too.

Schools are an agent of change in our society. This is where we plan the future of our country’s citizens. If the student is given a great environment, then it will be a turning point for their lives. We need to do a lot of work to make this environment conducive to this. We need to build values in kids that teaches them the concept of equality.

CHANGE MAKER

20

Voices From

the Playground

In 1966, the Kothari Commission report, considered one of independent India’s earliest formal recognition of teachers and the larger profession of teaching, famously stated, “The destiny of India is now being shaped in her classrooms.” And the most significant factor that influences the quality of education, the commission – headed by DK Kothari, the former University Grants Commission chief-added, is: Teachers.

There are approximately 9.7 million teachers across 1.5 million schools in India, a country considered one of the largest school education systems in the world. They’re mentors, knowledge creators and inspiration for millions of students. They shape the minds of tomorrow. But what makes them truly exceptional?

For this segment, we turned to the true judges in the classroom: The students! Click on this link or scan the QR code to see what they said.

Meet The

Contributors

Sohini Bhattacharya

Sohini Bhattacharya is the CEO of Breakthrough who has worked in the development sector for more than 30 years. She also co-founded Sanhita Gender Resource Centre in 1996, and is a founding member of the Coalition for Good Schools Voices from the South – a collection of leading practitioners and influencers committed to delivering access to a safe learning environment for children across the Global South. In The Lede – her recurring editor’s note in Engendering Education – Bhattacharya invokes the power of the everyday Savitribais of India, those unsung teachers who are truly the driving forces of gender transformative education.

Adhishree Parasnis

Adhishree Parasnis is the Director of Communications at Global School Leaders and has been working to bring wide-ranging experiences in design, research, facilitation, and community building in the education sector. Most recently, Adhishree was the Senior Strategist at Subu and Rakshit, a design-for-social-impact firm. For the second issue’s Cover Story, Parasnis is joined by her colleagues Sanya Sagar, the senior manager of programs at Global School Leaders, and Tejas Airodi, the manager of research there, to talk about how gender-inclusive leadership can change cultural norms, mindsets, and communities.

Ritwik Chakravarty

Ritwik Chakravarty is a community educator, trainer and the senior program officer at Humsafar Support Centre for Women, Youth and Queer Persons in Crisis. Based in Lucknow, Chakravarty has been working towards addressing gender inequality and inequity, especially among underserved communities in his hometown Lucknow who don’t have easy access to formal education. Their work includes LGBTQ+ awareness, often by repurposing gendered school textbook poems and activities. In Close Up, Chakravarty introduced Engendering Education to “Ritu” to talk about breaking gender barriers for kids and the importance of an inclusive language in classrooms that comes from acceptance as well as assertion.

Anita Bharti

Anita Bharti has been an educator for over 30 years and is currently the principal of Sarvodaya Kanya Vidyalaya in Delhi’s Timarpur electoral constituency. In India’s public schooling system, Bharti has been both a teacher and a critical leadership voice, pushing for caste and gender intersectionality in classrooms and making them truly inclusive and non-discriminatory. Bharti is also an anti-caste poet, writer and literary critic who brings Dalit feminism perspective into Hindi literature. In Change Maker, Bharti talks about the everyday violence in classrooms and how diverse leadership can build safe and equitable learning experiences for children.

22

COPYRIGHT

Engendering Education

Issue No.2

Editor-in-Chief:

Sohini Bhattacharya

Commissioning Editor:

Pallavi Pundir

Editorial Team:

Arunava Banerjee

Barsha Chakraborty

Epti Pattnaik

Pritha Chatterjee

Richa Singh

Design & Illustrations:

Aditi Dash

Website Design:

Arjun Khare

Hemant Mudgil

Sonalika Goswami

Published by Breakthrough Trust, New Delhi, 2024.

Breakthrough Trust,

Plot-3, DDA Community Centre, Zamrudpur,

New Delhi, Delhi 110048

![]() contact@inbreakthrough.org

contact@inbreakthrough.org![]() inbreakthrough.org

inbreakthrough.org

Download this publication for free at: engenderingeducation.in

Write to us at:

editorialteam@inbreakthrough.org

This publication is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike 4.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). To view a copy of this license, visit: www.creativecommons.org/licences/by-nc-sa/4.0/.

All photographs used with permission from the contributors and their respective organisations.

23