ENGENDERING EDUCATION

A Breakthrough Magazine

![]()

Empower. Educate. Transform.

Contents

07

The Anatomy of a Good School

Dipak Naker

13

What We Talk About When

We Talk About Sex

Sangeeta Saksena

‘The Power Structure Changes

When Children Speak Up’

Praveen Vempadapu

01

Editor’s Note

Sohini Bhattacharya

When I was in class 10, we got one of the most well-known physics teachers in our school, a legend in his own right in my city. Although there was huge excitement in class, the euphoria didn’t last long- at least among girls like me who were not STEM students. This teacher was incapable of making the subject fun and interesting, or even pedestrian for those not naturally inclined towards physics. The worst: half the class – the female part of it – hardly existed for him. If Rina or Swati answered his questions, all they got was a “Thank you, Rahul / Amit/Rajeev” (all names of boys) in return, as if that girl didn’t exist.

You may say this was just one teacher, but the fact that others, including the teachers never addressed this, or that most students admiringly passed it off as befitting his great reputation, shows that this behavior was normalized.

When we, at Breakthrough India, started designing interventions on making the school environment more safe and welcoming of all genders, I often thought of that class and that teacher. Research shows a significant gender gap in maths attainment among students even in the global north. Joseph Cimpian, the Associate Professor of Economics and Education Policy at the New York University, wrote that teachers tend to rate the boys as more likely to perform better in mathematics than girls even if both the genders are of the same race and socioeconomic status, perform equally well on mathematics tests, and whose behaviors and efforts are valued equally by their teachers. This kind of underrating starts from kindergarten through the third grade, resulting in significant gender achievement gap growth in STEM education.

THE LEDE

02

When we first started working in schools of Haryana in 2012, we noticed gender stereotyping at an early age, like when girls were asked to serve tea to the visitors while boys were asked to bring out chairs. In many schools, girls deal with sexist slurs, or being discouraged from playing during their periods, or have sermons read to them about the lengths of their skirts, or how friendly they’re being with boys. This also includes urban, elite schools. For boys, corporal punishment rules include any kind of labor intensive tasks as if girls are not capable of carrying weights! In rural schools in Uttar Pradesh, we found girls don’t have the vocabulary for aspirations. When parents don’t prioritise education for their daughters and schools offer discouraging interactions based on your gender, the result is often a crack in the system.

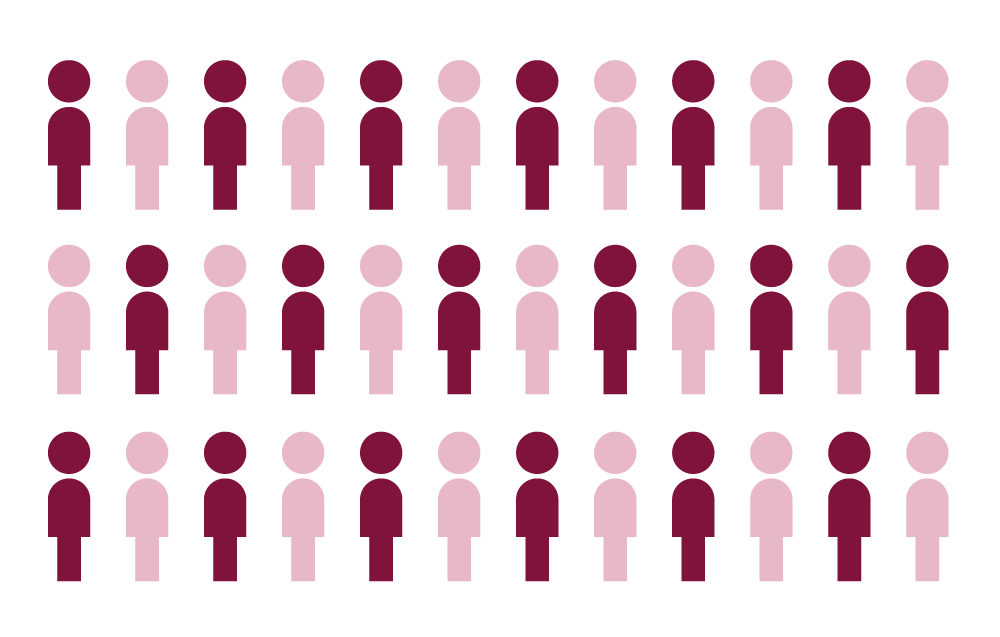

In 2020, an estimated 40%

of girls were out of school,

according to a report by both

UNICEF and the World Bank.

Every year in India, especially within the public school system, large numbers of girls enroll into schools. But a huge number drops out by the time they reach the age of 15. The reason is not always poverty. Strong gender norms contribute to dropouts in the secondary or higher education level. Studies also reveal how parents believe that private schools offer a better education, leading to better career prospects. Hence, they are more willing to pay for their sons’ education at private schools than their daughters’. This polarization of schooling – boys: superior, private schooling; girls: inferior, government schooling is creating imbalances that are severely gendered and has consequences not only for the self-esteem and identity of girls but also affects their future prospects of education and employment. So much in your educational journey depends on the kind of positive reinforcements you are receiving in your place of education for it to become valuable and meaningful for you. Are your teachers asking you questions in class? Are they encouraging you to work on the STEM subjects and making them interesting for you?

Are caste/race based slurs ever used in their interaction with you? Is menstruation a hush-hush subject in your school? Are you encouraged to interact with other genders without fearing retribution like shaming and scolding?

Gender equitable behaviors need to be intentionalized by every school leader and teachers if we are to reach gender equality and if all genders are to carve out aspirational futures for themselves. We need to work with the school community and the state administrative officers so that schools can realize their potential to be transformative spaces that can impact the future of large numbers of young people through its near universal reach. Schools are major contexts for gender socialization, in part because children spend large amounts of time engaged with peers and teachers in such settings. Schools can diminish gender differences by providing environments that promote gender

THE LEDE

03

equitable views, curiosity to ask questions, and better inter-gender relationships. Yet, so few education programmes are gender intentional in addressing the school system.

If India is keen on achieving gender equality goals, there is a need to focus on the role of education in doing so. We are already aware of the multiple positive benefits associated with it, such as strengthened economies and reduced inequality, more stable, resilient societies that give all individuals associated with it the opportunity to fulfil their potential.3 For schools to become gender transformative spaces, we need to utilize the whole school system – from policies to pedagogies to community engagement – to transform stereotypes, attitudes, norms and practices by challenging power relations, rethinking gender norms and binaries, and raising critical consciousness about the root causes of inequality and systems of oppression.

Breakthrough’s long-term vision is a gender transformative society where adolescents live a life free of discrimination and violence. A gender transformative school system goes beyond superficial acknowledgments of gender disparities; it aims to dismantle the societal constructs that perpetuate inequality and discrimination.

It recognizes gender as a spectrum, breaking free from binary definitions and embracing the diverse identities and expressions that exist. By doing so, it seeks to provide equal access to high-quality education for all individuals, regardless of their gender identity, expression, or social background.

This is not the work of one organization alone, we need a movement built around a strong narrative about a gender transformative education system. This requires collaboration and concerted efforts from educators, policymakers, parents, and communities. It entails integrating gender equality principles into educational policies and practices, providing ongoing training and support for teachers, and engaging with organizations and advocates specializing in gender equality. This magazine is our attempt to do that – to build an inspired community that wants to contribute to a movement that can address gender inequity and inequality at its roots. It will focus on what Breakthrough cares about the most and say it consistently, to be able to bring attention to something that is currently not being done specifically.

THE LEDE

04

The narrative needs to be built so that people will be inspired to engage with it and eventually feel a kinship with. It will define the themes and topics around which content can be created.

Our magazine will allow all user participants to co-create knowledge that then gets contributed back to the gender transformative education movement as a whole across the globe. This can be in the form of information on curricula that can be shared for specific subjects; where best practices for teachers and implementers across diverse settings can be shared: information on immersive trainings and self-assessments on gender across the school ecosystem are available; where shared research and evaluation methods and results are available and shared sustainability/outreach strategies are hosted and discussed.

Our first issue focuses on contributions from the Global South and not just India. We have Dipak Naker, co-founder of Raising Voices, an Uganda-based non-profit that works towards preventing violence against children and women, who campaigns for a seismic shift in the purpose of schools that not only enables children to reach their full potential, but also help them become the leaders of tomorrow. We also have Sangeeta Saksena, co-founder of Enfold Proactive Health Trust, an NGO that imparts life skills based on sexuality education and child sexual abuse awareness and prevention programmes. Praveen Vempadapu is the secretary and director of Kidpower India, an international NGO that provides safety training and support to vulnerable children in India.

Sohini Bhattacharya

Editor-in-Chief, Engendering Education

1.Joseph Cimpian, How Our Education System Undermines Gender Equity (The Brookings Institute, April 23, 2018)

2.Anupma Mehta, Need for Gender Transformative Focus in India’s Education Policy (The Economics Society, Sri Ram College of Commerce, May 29, 2020)

3.Anushna Jha and Mehrin Shah, Leveraging Education as a Tool to Achieve Gender Equality-Strategies and Signposts (London School of Economics and Political Science, April 8, 2020)

THE LEDE

05

The Anatomy of a Good School

Dipak Naker

Schools are seen as a critical investment for millions of children in the Global South and yet, the uncomfortable truth is that they’re often caught in unimaginative and violent environments that deprive them of opportunities to grow and think independently. Dipak Naker – the co-founder of Uganda-based non-profit Raising Voices, which creates evidence-based violence prevention programs in schools and communities – invites the readers to rethink the conceptual architecture of a ‘good school’, where the focus shifts beyond the metrics of education, to the experience of it.

COVER STORY

07

For many living in the Global South, sending a child to school is one of their highest aspirations. It is a repository for our highest ideal as humanity, an investment in bequeathing knowledge and skills to our children so they may live more fulfilling lives. That is why families sacrifice immediate income and labor, and children give up autonomy and time to attend schools. That is why we invest significant resources and goodwill in ensuring that children get an opportunity to attend schools.

Yet, the disappointing truth for many children is that schools are an empty promise. They go there full of hope and encounter constricting systems, overburdened teachers, and unimaginative environments that deprive them of opportunities to grow and blossom. They are controlled through the violence of corporal punishment, sexual harassment and bullying, and deprived of an opportunity for a

meaningful self-definition. As a result, large numbers of children are not thriving at such schools, and many are voting with their feet, emerging with disappointments and a diminished sense of their place in this world.

This violence is profoundly consequential. Its effect permeates every aspect of children’s lives – from when they will marry, the size of their family, to their physical, mental and economic health.

From social outcomes to life-span truncation, such a violence undermines the entire architecture of their possibilities. We could do better. We should do better. So why don’t we?

Part of the problem is that there are no easy answers or quick fixes. For many countries in the Global South, the magnitude of the problem is daunting. They have a young population in need of an investment and limited resources to respond to that need. The policy makers have other things competing for their fraying attention and paternalistic views about children and their place within our society undermines a sustained focus on this problem. In such a context, we are unlikely to come up with a magic bullet that solves the problem efficiently.

What we need in a multilayered response and an important part of that portfolio of solutions is reexamining the purpose of schools. It will require shifting from an instrumental view of a school to a more expansive conception of what school is for. The status quo signals that a good school teaches children how to score well on tests and obey instructions diligently. We all imbibe tropes of a good student as someone whose head is buried in books most of the time, whose discipline is measured by their test results. But what if we tried to characterize a good school as one that enables children to emerge to their full potential and access the full diversity of their possible selves?

COVER STORY

08

What if we expected

our schools to nurture

independent thinkers

rather than

compliant workers.

These metrics are important and necessary, but we should also pay attention to the actual experience of school; how children feel at their school, what values they imbibe, what the operational culture of school signals to children, and what impact that has on their sense of self and their prospects in their community.

A growing body of practitioners are beginning to take on this challenge and beginning to recognize that the work of creating a good school is integrally linked with the work of prevention of violence against children at school. Such work is not an outlandish or an impractical idea. It could be argued that in a modern, globally integrated economy, such a school is a necessity. If we are to give children going to public schools in the Global South a chance to be able to hold their own in the competition of ideas and innovation, if we are to enable them to take their rightful place with verve and tenacity of thought leaders, we need to equip them with these capabilities. Without such rethinking, we are likely to condemn them to subservience, and subjugate them perpetually to the status of a global underclass.

COVER STORY

09

If you are a policymaker or an educator, you may well wonder if this is facile rhetoric, with no reference to reality. You may wonder about the practicality of such ideas when an educator is facing a rowdy class of 75 students, or an under-resourced and overstretched operating environment. No one in their right mind would say this is an easy problem to solve. The magnitude of the problem is daunting, and the fruits of any intervention are not going to be visible immediately. But that should not delay us from beginning the work. The status quo is only fomenting stagnation, and a pivot is needed to begin the work of laying the foundations for a way forward. There are initiatives out there that are beginning to break ground for the long road ahead. If you are interested in creating such schools, below are five key ideas that are a part of that starting point:

Linking the Experience of Education With the Outcome We Seek

The education sector is still reluctant to own the problem of violence in schools because of an underlying assumption that violence against children is a social problem that is best addressed in the home or the community. Therefore, the thinking goes: Limited time and resources of a school should be reserved for addressing tangible outcomes, such as acquisition of cognitive skills and fostering learning outcomes. In such a climate, any credible intervention that goes counter to this status quo needs to persuade educators and officials that the psychological health of learners has a profound influence on their process of learning.

This requires popularizing an expansive vision for schools and enlisting diverse stakeholders to promote such a vision. It requires galvanizing a significant proportion of actors within the education delivery system to endorse, amplify, and implement the central ideas underpinning the intervention. It requires popularizing an expansive vision for schools and enlisting diverse stakeholders to promote such a vision. Without investing in developing such an ‘opinion infrastructure’, the efforts won’t succeed.

Innovate the Learning Process, Delink Fear with Learning

Many school practices are mired in a deeply hierarchical structure and are profoundly influenced by outdated models of the learning process. A significant proportion of education practitioners believe that fear and stress are the primary psychological levers for fostering learning in students. To dismantle this assumption and create a more progressive approach informed by evidence requires input at the policy, oversight, as well as at school levels. It also requires engagement of parents and opinion leaders at the community level using tools, learning materials, and learner-centric processes that make the case that when the environment is inclusive, respectful, and safe, more learners are able to take the risk of exploring new ideas and integrate them in their emerging worldview.

COVER STORY

10

Ideas That Enter a School Do Not Stay at School

Each school gains support from and conversely has an influence on how ideas enter a community. For example, schools may have a mandate to act as an incubator of fresh ideas and innovation, and therefore the community is likely to tolerate a level of exploration that it may not in the home, or elsewhere in the community. Therein lies an opportunity to Introduce a carefully designed innovation aimed at fostering a school-wide reflection on values and norms that determine attitudes and behavior. The aim here is to influence the school’s operational culture instead of targeting a narrow range of behaviors that could be identified as violence, resulting in a longer-term and sustained outcomes.

Offer Ideas, Not Directions

Instead of disembodied messages or isolated behavioral prescriptions, offer an overarching vision of the journey with easy milestones that can be managed and navigated by a significant proportion of the school system. Offer a process exploration and reflection instead of a blueprint for action. Integrate ideas for collective learning and a tracking system that allows the entire school to witness and recognize progress. If the process is efficient and elegant, it will allow the psychologically important phenomenon of ownership and agency to emerge, and it will likely create preconditions for sustainability.

Count on Local Leaderships

The intervention may have been conceived elsewhere, but the implementation has to be led by people near the school. Thus, the design has to embody clear, meaningful, and leadership roles for multiple members of the school community, and it has to be flexible enough to accommodate diversity of skill and capacities, Including those of children. The ideas promoted by the intervention may be innovative, but the activities have to be familiar and linked to behaviors and values that speak to the identifiable values that the majority of the school aspires to.

Violence is Systemic, Not Individual Behavior

Implicit in this whole school approach is the idea that prevention of violence is about addressing the system rather than behavior at an individual level. The unit of intervention is the school and not the individual teachers or students. The outcome being sought is not the specific behavior change (though that will emerge) but transformation of the operational culture that fosters a new way of valuing and relating to each other’s dignity as humans.

Such a culture is not only likely to reject violence but also provide fertile ground for developing agency, a sense of citizenship and yes, an expansive cognitive toolkit that may be conceptualized as learning outcomes. Such an approach yields long-term outcomes not only from the narrow lens of education but of life outcomes. Isn’t that what education is for?

COVER STORY

11

What We

Talk About

When

We Talk

About

Sex

Much before India passed the Protection of Children Against Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act in 2012, Dr Sangeeta Saksena had been spending the better part of her professional life trying to understand what young Indians-including children as young has first graders – think of sex and sexuality. The responses surprised her. The co-founder of Enfold Proactive Health Trust in Bengaluru, Dr Saksena joins the inaugural edition of Engendering Education to reveal the sexual attitudes of one of the world’s largest child and adolescent populations, and why it’s imperative for India to have sex and physical safety education from a wider and restorative lens.

CLOSE UP

13

As a gynaecologist working in a large teaching hospital in Bengaluru in the year 2000, Dr Sangeeta Saksena was accustomed to seeing young Indians walk in with a myriad of issues: from unwanted pregnacies to HIV. Then an assistant professor at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at St John’s Hospital in Bengaluru, Dr Saksena, along with her friend and colleague Dr Shaibya Saldanha, would often wonder if these issues are due to lack of scientific information on sexuality. In order to find the root cause, Dr Saksena decided to speak to adolescents. Through comprehensive interactions in 2001 with hundreds of students studying in eighth, ninth, and tenth grade in a school in Koramangala, Dr Saksena and Dr Saldanha determined what was amiss. Their findings, which was also published in Indian Journal of Paediatrics, surprised them.

“It wasn’t as much the lack of information [on sex] as much as lack of self-confidence and self-respect among young Indians – towards themselves and their bodies,” Dr Saksena told Engendering Education. They, then, went to grade 5, during which they learnt how poor self-esteem starts so young. “It’s ingrained in us so young because of our cultural practices of comparing, for instance, skin color or our bodies,” she said. Dr Saksena then decided to speak to an even younger demographic: Grade 1. “That is when we realized the extent of child sexual abuse (CSA) in India,” revealed Dr Saksena.

India is home to over 444 million children, one of the world’s largest child and adolescent populations. The country has some of the most stringent laws to protect children against many crimes including sexual abuse under the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act, which was passed in 2012. The 2007 study on child abuse by the Ministry of Women and Child Development, Government of India had found that 53.2 per cent of the over 12,000 children surveyed had suffered some form of sexual abuse. More recent National Crime Records Bureau data shows that this number is increasing.

When Dr Saksena co-founded Enfold Proactive Health Trust with Dr Saldanha, she knew not just the problem, but also the extent of it.

One in every

two children

in India is a

victim of CSA.

A 2017 survey by humanitarian aid organisation World Vision India.

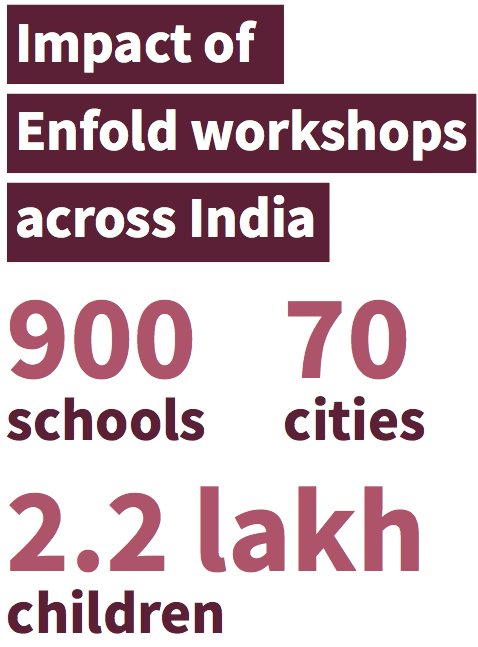

Through Enfold, Dr Saksena sought to create safer, respectful, and gender equitable spaces through preventive education, awareness and rehabilitative support for survivors of CSA. And one of the key tools to do that was the creation of an indigenously-designed, age-appropriate, cultually-relevant curriculum on sexuality and personal safety education for children and adult stakeholders. Along with Dr Shekhar Seshadri, the doctors also co-authored On Track-a workbook series on life skills and personal safety for school children from grade 1-10 (published by Macmillan Education India). These workbooks also include information manuals for parents and teachers.

Enfold is the first organization to offer personal safety as part of the curriculum from grade 1 onwards in Indian schools, says Dr Saksena. This was much before POCSO came into effect. But in a country like India, where stigma and bias against sex education has led to much backlash against educators over the years, Dr Saksena and her team promoted children’s and adolescents’ safety and wellbeing, keeping ground realities in mind.

CLOSE UP

14

“Given the cultural backgrounds of most of these children, we decided to use words like ‘sussu’ and ‘potty’ for private parts until grade 4,” said Dr Saksena. “As gynaecologists, we can say anatomical terms like vulva and penis, but in this case, we decided it’s up to the parents to give proper names of genitals when they deem it fit for their children. Our aim was to give an unambiguous vocabulary to small children to ask questions, report discomfort and any unsafe behavior.”

The resistance to sex education in India has been consistent. In 2007, India saw massive protests in six states against inclusion of sex education in class 10 syllabi by the state boards. In 2009, several Indian states suspended sex education program designed to combat the spread of HIV/AIDS after protests by lawmakers who said it would corrupt young minds. Dr Saksena said that such backlash could have been partly due to the use of curricula and materials that were not indigenously developed and were not adapted to Indian socio-cultural milieu. However Enfold’s work was not affected – in fact it grew.

Over the years, the Enfold team has incorporated some key values into their approach:

- Education in gender equity, sexuality, and personal safety can build acceptance and respect for the body and its sexual and reproductive functions and the diversity in gender and sexuality; promote safe behavior towards each other and thereby prevent sexual abuse and gender based violence against children and adults alike.

- One can heal from child sexual abuse and gender based violence with professional help.

- It takes community effort and child sensitive systems to keep children safe.

- People of all gender and sexual identities have equal right to safety and dignity – and individuals, families, communities, and our laws, policies, and systems can promote this.

CLOSE UP

15

The organization’s Support and Rehabilitation team supports close to 75 children who have reported sexual violence. In 2022, the organization published a Handbook for Support Persons to work with child victims under the POCSO Act. In 2016, Dr Saksena and Dr Saldanha created the Suvidha Project – the first initiative of its kind in India that offers education on gender equity, sexuality, and personal safety to children with disabilities. The ‘Suvidha Suraksha’ kit is for the parents and teachers of children with intellectual disabilities, autism, and related conditions. Enfold offers them training in the use of the kit, building their capacity to offer sexuality education in the context of disabilities. The Suvidha Sparsh kit is also available for use by children with visual and hearing impairment.

The internet and social media has played a big role in exposing young Indians to age inapproprate sexual content that is, at times, inaccurate, unscientific, and violates other’s rights. “Social media puts pressure on children,” said Dr Saksena. “In earlier days, we

CLOSE UP

16

Recommendations have been made by the Verma Committee and others, and the CBSE curriculum also includes it. “But we need a wider perspective that is gender transformative, which includes disabilities, and is restorative. Some forms of education also focus only on the physical aspects rather than emotional,” said Dr Saksena. “There’s a misconception that sexuality education begins at 12 or 13 years of age. It actually starts much younger, from the time the child begins to understand words and expressions. We need more work.”

Right now, Dr Saksena and her team are advocating to include comprehensive sexuality and personal safety curriculums in all schools and colleges, across all streams. “My personal aim in life is to see that this education is made easily accessible and reaches everybody in a language and manner that is comfortable for them,” said Dr Saksena.

1.Protest Against Sex Education, Times of India (2007)

2. Conservatives Obstruct Sex Education in 6 States, Amelia Gentleman, New York Times (2007)

3. How Indians View Gender Roles in Families and Society, Pew Research Center (2022)

4. Health Secretary launches SAATHIYA Resource Kit and SAATHIYA SALAH’ Mobile App for Adolescents, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (2017)

CLOSE UP

17

‘The Power

Structure

Changes

When Children

Speak

Up’

Praveen Vempadapu

In 2007, a National Study on Child Abuse, released by India’s Ministry of Women and Child Development, with support of UNICEF, Save the Children, and Prayas, found that over 53 per cent of the surveyed children face sexual abuse. Struck by the distress among India’s youngest population, Praveen Vempadapu went on to found the India chapter of Kidpower International in 2007 and, through workshops and educational support, decided to support hundreds of children every year. In this interview with Engendering Education, Mr Vempadapu lays bare the processes of Kidpower India’s work.

CHANGE MAKER

18

How did you begin your journey as a child rights activist and director of Kidpower India?

I have a background in engineering, management, and development studies. Being with a non-profit was not initially my idea but I was working with a women’s group as part of my MBA study and I thought I would do a non-profit course. I ended up in the Netherlands to do a masters course in development studies from the Institute of Social Studies. After I came back to India, I realized that I wanted to do something with children and children’s education. In 2007, there was the National Study of Child Abuse released by the Indian ministry of women and child development. It found that around 50 per cent of children – boys and girls have gone through sexual harm, both physical and emotional. What struck me more is that most of the time, it’s not reported -73 per cent of them.

Indian society has a deeply inherent power structure: You have to respect your elders. There’s nothing wrong with this notion but when someone abuses that valuable relation of a parent or teacher or a family relative, how do you stand up for yourself? That was the important point I was looking at when I wanted to start something in India. Apart from the abuse statistics, how much is being reported and how many children speak up?

What is the most important aspect of facilitating trainings with children?

What’s important to me while training is not just instilling confidence in standing up to abuse, but the practical approach of it through the workshop model of training. I went to the US and joined Kidpower International’s trainings. They provided us with all the materials and training to adapt to the Indian circumstances. The program also targets the disabled and differently abled, as well as across LGBTQ+ spectrum and non-binary identities. For India, I created a program specifically for girls, which isn’t there in the U.S. It’s called ‘GirlPower’. It’s the same lesson plan and skills but adapted to the circumstances of women and girls’ lives in India. This program has been translated and adopted by other countries like Lebanon, Vietnam, and Mexico.

What does the Kidpower training entail?

The first thing we teach at Kidpower is being aware of the circumstances and being confident. We talk about how to use your body to set boundaries in a strong way and how to use your voice to say no. This is a practical training so we take real-life examples from the lives of the children.

In India, there’s quite a taboo around sexual abuse. How did you start approaching schools with Kidpower’s safety trainings?

We mostly focused on Visakhapatnam. We approached the schools and non-profits. The best part is that our trainings are free and they are also available online. So many schools are open to our trainings. We conduct around 20 trainings a year.

One of the guiding principles of Kidpower is that safety is priority, and other people’s embarrassment, inconvenience, or offence is not important. It’s easily said but in a society where children grow up with the notion that they’ve to respect elders and not talk back, how do you first ensure your safety? This is the power relation between children and elders. We train people how to overcome this. We train multiple stakeholders but the elders, like the parents and teachers, should enable a safe space for that to happen by understanding the power relations and believing the kids.

19

Could you talk about the impact of your trainings?

The major change at institutional levels I found is that children are more willing to share with you if there’s an abuse situation. We’ve seen the power structure change once children speak up. At any abuse prevention training, if you give a message to the girls and boys that there’s no tolerance for abuse, they immediately come to you and complain about the abuse, including from teachers or through corporal punishment. After that, when they need help, we create avenues for them to speak up and get help. This helps schools address the problem of abuse.

Among all the issues Kidpower addresses, what concerns you the most?

In education, we work a lot with slum children who are engaged in rag picking and begging. I would say one of the most pressing problems I have found in such circumstances is how girls are pushed out of schools. Often in such settings, girls as young as 6 years old have to stay back to take care of other children. Then a big challenge is when girls are 15 or 16, an age that is an opportunity for their family. Sometimes, these girls go on a family vacation and just fall off the map, only to come back as a married woman. At Kidpower, we have a scholarship program for girls to address these dropouts and problem of child marriage.

In many circumstances, we have found that when there’s a change in family circumstances, the family prefers to put the girl in a government school while keeping the boys in a private school. Again, we have noticed dropouts in such cases.

Having seen these patterns, we try to address this from a non-profit point of view by providing scholarships to girls and running special learning centres. We also counsel the parents and girls to study further.

What has been the most memorable part of your journey with Kidpower?

When I work with visually challenged children, they have different visual levels. How they practise and use it while travelling or outdoors, I found that very touching. During training, I’ve had a child come to me and say that while travelling in a train, someone tried to abuse them, they shouted and the person ran away. When children come to us to tell us how they used the skills we taught them in real life, it feels very rewarding.

Does the prevalence of abuse on social media make things challenging for you and the work Kidpower does?

The principles of our program remain the same even when we talk about social media with the children. You’ve to keep adapting. Such as, when we talk about social media, the safety principles are the same. We ask questions like: Who’s a stranger? What is the stranger danger? What is personal information? Who are you sharing it with? Social media is a huge challenge for safety.

What is your vision for the future of safety for children?

A coalition of good schools is a good way to reach more children. We’ve had the 2007 report of abuse and then, in 2011, the National Education Policy came into effect. It spoke about abuse prevention in schools and stated that abuse like corporal punishment isn’t allowed. But nothing has happened after that. There’s been no other work or interpretation of policies after that. Something needs to be done at the policy level to bring impact in the lives of children.

CHANGE MAKER

20

Meet The

Contributors

Sohini Bhattacharya

Sohini Bhattacharya is the CEO of Breakthrough who has worked in the development sector for more than 30 years. She also co-founded Sanhita Gender Resource Centre in 1996, and is a founding member of the Coalition for Good Schools – Voices from the South – a collection of leading practitioners and influencers committed to delivering access to a safe learning environment for children across the Global South. In The Lede – her recurring editor’s note in Engendering Education – Bhattacharya introduces the readers to the magazine as well as its longstanding vision to bring together diverse voices that reimagine education as a powerful tool for societal transformation.

Dipak Naker

Born in Tanzania, Dipak Naker is the co-founder of Uganda-based non-profit Raising Voices, and currently works as the Executive Director of the Coalition for Good Schools. His work draws heavily from observing firsthand the profound ways interpersonal violence impacts women and children. For the last 20 years, Naker and his organisation have been creating a comprehensive approach to violence prevention, especially in schools. For our Cover Story section – which invites industry experts and practitioners to author experiences in creating pedagogical interventions for equal and intersectional education practices – Naker invites us to rethink the experience of education.

Sangeeta Saksena

Dr Sangeeta Saksena founded the non-profit Enfold Proactive Health Trust with her friend and colleague Dr Shaibya Saldanha in order to address one simple question: What do young Indians know about sex? Her questions led to shocking revelations about the scale of child sexual abuse in the country. In the Close Up section – wherein we put the spotlight on those driving critical, and sometimes uncomfortable, conversations – Dr Saksena speaks about Enfold’s journey in designing and implementing an indigenous curriculum on sexuality and personal safety education for school and college students in India.

Praveen Vempadapu

In 2007, Praveen Vempadapu read the National Study on Child Abuse released by the Indian government, which revealed shocking revelations on the extent of child sexual abuse in India. The same year, his determination to address this systemic problem brought Kidpower International, a global nonprofit leader in teaching child protection and personal safety skills to adults and children, to India for the first time. In Change Maker – a section that features an intimate conversation with child rights and education experts – Vempadapu talks about what Kidpower India does, and how it tackles the problem of abuse in schools.

21

COPYRIGHT

Engendering Education

Issue No.1

Editor-in-Chief:

Sohini Bhattacharya

Commissioning Editor:

Pallavi Pundir

Editorial Team:

Arunava Banerjee

Barsha Chakraborty

Epti Pattnaik

Pritha Chatterjee

Richa Singh

Design & Illustrations:

Aditi Dash

Website Design:

Arjun Khare

Hemant Mudgil

Sonalika Goswami

Published by Breakthrough Trust, New Delhi, 2023.

Breakthrough Trust,

Plot-3, DDA Community Centre, Zamrudpur,

New Delhi, Delhi 110048

![]() contact@inbreakthrough.org

contact@inbreakthrough.org![]() inbreakthrough.org

inbreakthrough.org

Download this publication for free at: engenderingeducation.in

Write to us at:

editorialteam@inbreakthrough.org

This publication is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike 4.0 Unported (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). To view a copy of this license, visit: www.creativecommons.org/licences/by-nc-sa/4.0/.

All photographs used with permission from the contributors and their respective organisations.

22